A fly known to parasitize American bumble bees and wasps has recently been discovered parasitizing California honey bees, causing bees to abandon their colonies in the night. The investigators, who published a report this week in PLOS 1, think that the parasite's jump to honey bee hosts happened recently. Commercial transport of potentially infected bees to new areas needs to be stopped immediately to prevent the global spread of this serious threat to food production and the environment.

Bees parasitized by the phorid fly became disoriented, "turning into zombies", flying out into the night to die the next day. Parasitism was widespread in the study area near the San Francisco Bay. Parasitism was found at 77% of the sites they investigated. The highest rate of parasitism was 91% of the nocturnally active bees at one site.

Parasitism was associated with high rates of viral infection in the bees studied. Because the virus was also found in the flies, the scientists suspect that the parasitic flies are vectors for bee diseases. Colony collapse disorder continues to be considered caused by multiple factors, but the phorid flies may involved in several factors.

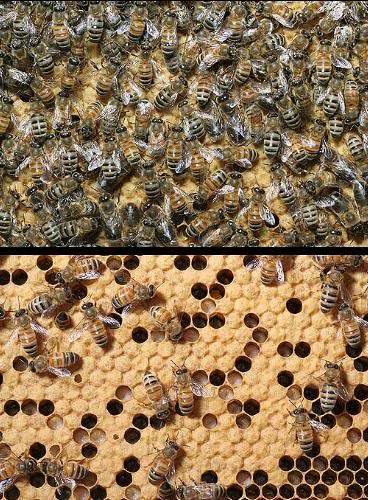

| Healthy vs Unhealthy colonies hat tip to Wee Mama for image source Image may be NSFW. Clik here to view.

We found widespread parasitism by A. borealis amongst 7,417 honey bees and 195 bumble bees (177 Bombus vosnesenskii, 18 Bombus melanopygus) sampled from San Francisco Bay Area localities. In all, 77% of our sample sites (24 of 31) yielded honey bees parasitized by A. borealis. |

The scientists sternly warn the public of the severe risks posed by the parasitic flies.

| The host shift from bumble bees to honey bees has potentially major implications for the population dynamics of A. borealis. Bumble bees live in relatively small colonies that last only a single season with only queens overwintering. Honey bees, on the other hand, live in much larger colonies with tens of thousands of individuals living in hives that are warm even in winter. If these flies have or can gain the ability to reproduce within hives they could greatly increase their population size and levels of virulence. Moreover, hundreds and sometimes thousands of commercial honey bee colonies are often found in close proximity to one another in agricultural areas. Such high host density might lead to population explosions of the fly and major impacts on the hives they parasitize. Further, A. borealis is already widely distributed across North America [14] (Figure 1). ..... Apocephalus borealis may also be a threat to native pollinators since it parasitizes a number of bumble bee species and paper wasps (Vespula spp) [13], [14]. Wild bumble bees are experiencing substantial declines in North America [44], [45]. So far, attention has focused on emerging pathogens such as Crithidia bombi and Nosema bombi. In the laboratory, bumble bees parasitized by A. borealis show a dramatic reduction in life span compared to unparasitized bees [13]. The high rate of parasitism in some of our samples of foraging bumble bees and previous high parasitism rates from Canada [13], suggest that parasitism by A. borealis, especially in combination with infection by emerging pathogens, could place significant stress on bumble bee populations. If so, phorid parasitism or pathogen transmission to bumble bees might contribute to a cascade of effects in plant and agricultural communities that rely on bumble bees as pollinators. Furthermore, the domestic honey bee is potentially A. borealis' ticket to global invasion. Establishment of A. borealis on other continents, where its lineage does not occur, where host bees are particularly naïve, and where further host shifts could take place, could have negative implications for worldwide agriculture and for biodiversity of non-North American wasps and bees. |

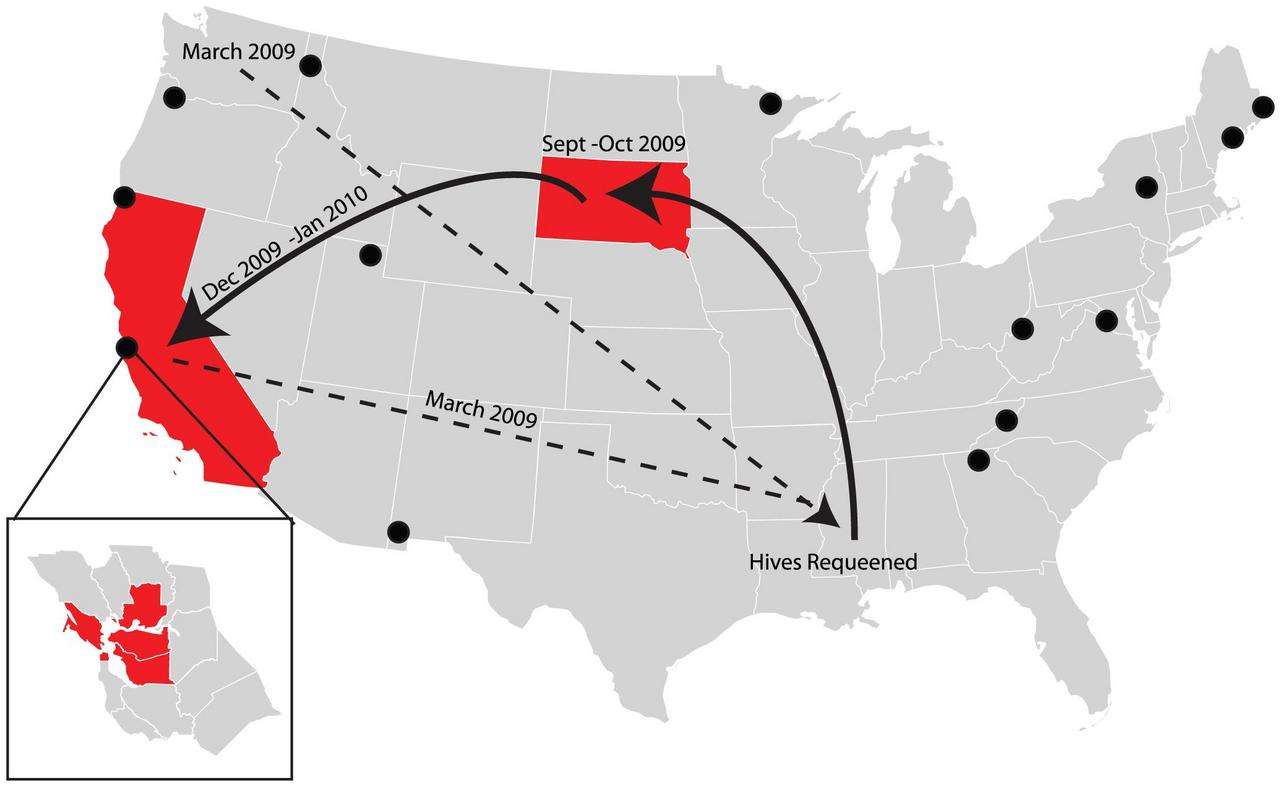

Apparently, commercial transport of bees has already spread the parasites to multiple states in the United States.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Distribution of phorid-infected honey bees sampled in this study (red).

Inset shows the San Francisco Bay Area counties where we found phorid-parasitized honey bees. The routes of commercial hives tested are indicated (arrows), where dotted lines represent states the hives crossed before viral microarray testing and solid lines represent the route of hives during the period of microarray testing. Sites where A. borealis was previously known [7] are indicated by black dots.