This year's Nobel prize in Chemistry will be awarded to Israeli scientist Daniel Shechtman for his discovery of quasicrystals, metallic alloys with atoms arranged in orderly, infinite, aperiodic, crystal-like patterns with theoretically forbidden (typically 5 fold) symmetry. This form of matter was believed to be impossible to create. Schectman made his discovery while on sabbatical at the U.S. National Bureau of Standards April 8, 1982 . He was laughed at.

"I told everyone who was ready to listen that I had material with pentagonal symmetry. People just laughed at me,"

When he returned home, Shectman was kicked out of his university research group but found a new group. He then moved to Israel where he found someone he could publish with, but his paper was rejected. He got it published on the second try, but his results were mocked and derided. Double Nobel winner Linus Pauling said

"Danny Shechtman is talking nonsense. There is no such thing as quasicrystals, only quasi-scientists."

Today, Dr Shectman is preparing to receive the Nobel prize.

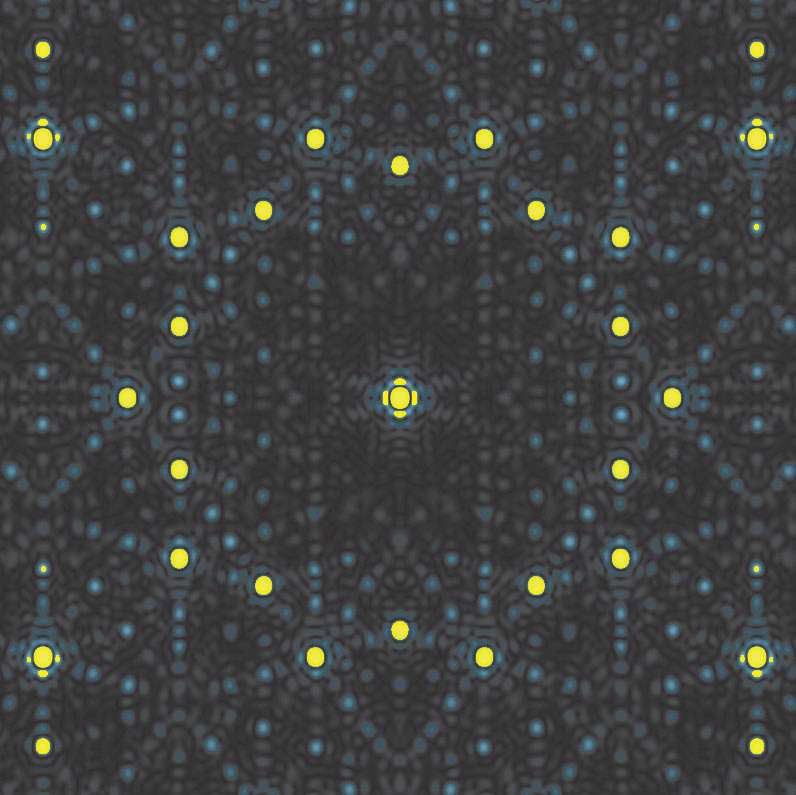

A quasicrystal of silver aluminum similar to the first quasicrystal of magnesium aluminum discovered by Nobel prizewinner Daniel Shechtman. Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

A quasicrystal of silver aluminum similar to the first quasicrystal of magnesium aluminum discovered by Nobel prizewinner Daniel Shechtman. Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

The long answer is: no one is sure. But the short answer is straightforward: a quasicrystal is a crystal with forbidden symmetry. Forbidden, that is, by “The Crystallographic Restriction”, a theorem that confines the rotational symmetries of translation lattices in two and three-dimensional Euclidean space to orders 2, 3, 4, and 6. This bedrock of theoretical solid-state science—the impossibility of five-fold symmetry in crystals can be traced, in the mineralogical literature, back to 1801—crumbled in 1984 when Dany Shechtman, a materials scientist working at what is now the National Institute of Standards and Technology, synthesized aluminium-manganese crystals with icosahedral symmetry.The term “quasicrystal”, hastily coined to label such theretofore unthinkable objects, suggests the confusions that Shechtman’s discovery sowed. What’s “quasi” about them? Are they sort-of-but-not-quite crystals? Solids with some sort of quasiperiodic structures? For that matter, what is a crystal?

Since the discovery of x-ray diffraction in 1912, a crystal’s identifying signature has been sharp bright spots in its diffraction pattern; that’s how Shechtman knew his were special. If it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it’s a duck: charged in 1992 with

formulating a suitably inclusive definition, the International Union for Crystallography’s newly-formed Commission on Aperiodic Crystals decreed a crystal to be “any solid having an essentially discrete diffraction diagram.” In the special case that “three dimensional lattice periodicity can be considered to be absent,” the crystal is aperiodic (http://www.iucr.org/...).